The Philippines is facing a chronic health care crisis as there are simply not enough doctors for its people.

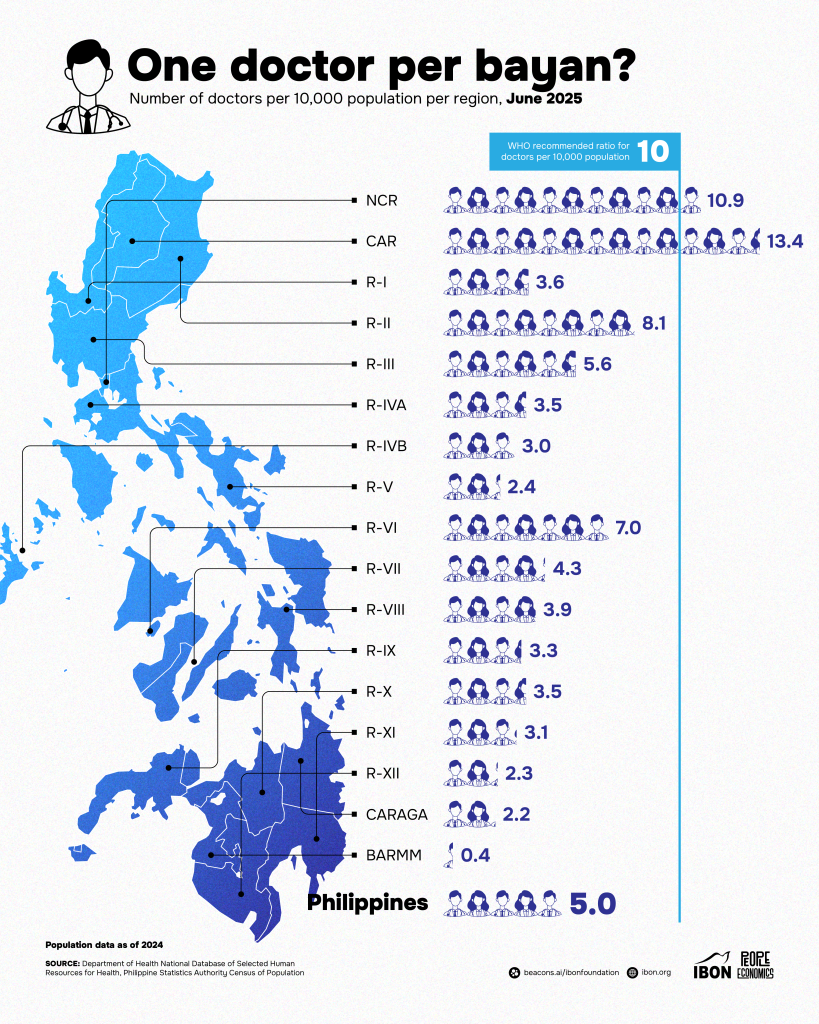

A recent study by IBON Foundation revealed that only two of the country’s 17 regions meet the World Health Organization’s (WHO) recommended ratio of 10 doctors for every 10,000 people. Everywhere else, the gap is wide and growing.

The Cordillera Administrative Region leads with 13.4 doctors per 10,000 population, followed by the National Capital Region with 10.9.

But beyond these outliers, most regions lag far behind as CARAGA has only 2.2, Eastern Visayas 3.9, and Zamboanga Peninsula 3.3.

Nationwide, the average is a mere 5 doctors per 10,000 people. The Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) has the lowest ratio of all, with just 0.4 per 10,000, an alarming figure that underscores the inequities between urban centers and rural, remote, or conflict-affected areas.

The WHO standard is considered the bare minimum for adequate health care access. Falling short translates to overstretched hospitals, longer queues, overworked physicians, and — ultimately — poorer health outcomes.

With the country’s growing population and repeated bouts of public health crises from dengue outbreaks to the COVID-19 pandemic, the deficit of doctors could push an already fragile system to the breaking point.

Doctors to the Barrios: A Lifeline, But Not Enough

As they said, a nation short on doctors as the lives sit at the margins of care.

When she was still a medical student, Dr. Rita Mae C. Ang-Bon caught a glimpse of how deep the health care disparities ran.

“During that time, it was more of an adventure for me, but I gained insights on the health care disparities and developed this deep sense of service for the people,” Ang-Bon recalled.

Her commitment led her to join the Department of Health’s flagship Doctors to the Barrios (DTTB) program after finishing her studies.

“During my 4th year of medical school (clinical clerkship), I applied for and got accepted into a private scholarship whose return service agreement is to serve for at least two years under the DOH’s Doctors to the Barrios Program.”

Ang-Bon was assigned to an island municipality. With little preparation, she was thrust into an environment where resources were scarce, infrastructure was crumbling, and she was, often, the community’s sole lifeline.

“When I arrived at the Rural Health Unit, it was mostly dilapidated and lacked the necessary equipment and supplies to efficiently operate,” she said. Electricity ran only from 5 p.m. to midnight. Antibiotics, IV fluids, and other life-saving medications were in short supply.

“In the barangays, there were no health stations, so we hold our preventive health clinics inside barangay halls, under the mango tree in front of sari-sari stores or in the house of our BHWs.”

However, children bore the brunt of this scarcity. “My area was among the top municipalities nationwide in terms of highest prevalence of underweight, stunting and wasting during that time,” she said.

In addition, maternal care was another uphill battle. “Most pregnant women there preferred to deliver their babies through traditional birth attendants, and they would only seek help of a doctor when there are complications or difficulties in the delivery.”

For Ang-Bon, her stint was a trial by fire that underscored the reality behind the statistics: rural municipalities often had no permanent doctors. They depended on government deployments — contracts that rotated every few years.

Wearing Many Hats

But the problem goes beyond the typical scenario.

As the only physician in her municipality, Ang-Bon was not just a doctor. She was also an administrator, manager, and community organizer.

“I am ‘on call’ 24/7 whenever I am on the island,” she said. “Oftentimes, in the middle of the night, I would hear motorcycle engines and knocks on the door of the house where I lived at that time.”

Her workload extended beyond treating patients. She supervised staff, managed programs, and trained local health workers. “I capacitated the deployed nurses, BHWs and BNSs, and even the administrative and clerical staff of our unit. All of them know how to take vital signs, how to provide basic first aid, how to screen for referrals and even provide health education.”

Even life-and-death cases demanded improvisation. She recalled a pregnant patient with dangerously high blood pressure, suspected pre-eclampsia, and no prenatal check-ups. The rural health unit lacked the medications and equipment needed for high-risk deliveries.

“During that time, fortunately I was able to call my mentor from the PGH who an OB specialist is. She guided me through to protect the child and the mother with the available resources that we had at the facility,” Ang-Bon said.

Transporting the patient to a provincial hospital was itself an ordeal. Fishermen had to wait for the tide to come in before a boat could leave. Hours later, the patient arrived at the provincial hospital, just in time to deliver a healthy baby.

“It was a very long night that I would never forget.”

A Doctor’s Day-to-Day: Overwhelmed in Mindanao

Rural communities in the country continuously endure crisis as doctors remain scarce.

For Dr. John Myco Ermac, a general practitioner in Misamis Oriental, the doctor-to-patient ratio isn’t just a statistic as it defines his daily struggles.

“When I was responsible for too many patients at once, it became difficult to give each case the time and attention it truly deserved,” Ermac said.

“I often found myself rushing through consultations, juggling multiple priorities, and feeling constantly behind on documentation.”

The strain was worsened when patients couldn’t afford referrals.

“Many of them work on a day-to-day basis. Although hospital bills are free in public hospitals, the cost of daily transportation to and from their hometown, along with other necessary expenses, makes it very difficult for them to accept transfers to higher institutions.”

In addition to this, infrastructure added another layer of difficulty.

“The lack of reliable electricity affected the use of essential medical equipment, proper storage of medicines, and overall clinic operations. Limited internet connectivity hindered communication with specialists for consultations, delayed access to patient records, and complicated referral processes.”

In remote barangays, a one-way ride could cost P300. Roads turned to mud in heavy rain, isolating entire communities. And so for Ermac, this meant delays in treatment and missed opportunities to save lives.

The Broader Picture: Why the Shortage Persists

The Philippine Medical Association (PMA) acknowledges the stark disparities. While around 6,000 doctors pass the licensure exam every year, most gravitate toward urban centers or leave for better-paying opportunities abroad.

“Being an archipelagic country, we already have a problem with traveling from island to island more so there is also disparity of the level of health facilities available in the geographically isolated areas,” said Dr. Hector Santos, Jr., PMA president.

“Another factor to decide place of medical practice is the better opportunity for the doctors to support their family, better housing and education opportunities for the children,” he added.

The result: rural areas remain chronically short on physicians. Programs like Espesyalista sa Bayan and DTTB have helped, but only as temporary fixes.

“I am glad to report that slowly we have more specialists going back to the provinces to serve their community,” Santos said, but emphasized much more needs to be done.

A Question of Priorities

IBON Foundation has warned that government spending priorities do not match the scale of the health crisis.

The proposed 2026 national budget increases health spending only marginally. Despite the president’s pledge of free health care, medical assistance for indigents was slashed by more than 40%, raising doubts about the government’s ability or willingness to keep its promise.

Some 43% of health expenses in the Philippines are still out-of-pocket, leaving millions vulnerable. To truly deliver universal health care, experts say the government must boost health spending to at least 3% of GDP, which is nearly triple the current allocation.

Consequences: Trust at Risk

For patients, the shortage of doctors could potentially erode trust in the healthcare system.

“When patients experience long wait times, delayed treatments, or are unable to access specialized care locally, they may feel neglected or underserved,” Ermac said.

“This can lead to frustration and skepticism about the quality and reliability of healthcare services.”

Some turn to traditional healers. Others avoid seeking care until conditions worsen — outcomes that ripple into higher mortality, more preventable diseases, and heavier burdens on already packed hospitals.

Ang-Bon, reflecting on her years as a barrio doctor, said her experience is far from unique. “My story was more than 12 years ago, but I firmly believe that even up to this day, there are still similar stories of other doctors serving in the communities.”

She believes medical education itself must be reshaped. “There is a need to review and maybe revise medical curriculum with the aim of developing and producing physicians who will serve in the communities to achieve the promises of universal health care.”

The Way Forward

Both doctors agree that the crisis isn’t just about numbers. It’s about equity, infrastructure, and political will.

“Rural and disadvantaged areas need more support, not only in numbers of healthcare professionals but also in resources and systems that make care truly accessible,” Ermac said.

“Investing in these communities means investing in the health and future of the entire country.”

For Ang-Bon, the answer lies in strengthening primary health care teams and empowering communities.

“Improving health outcomes require dedicated health professionals and community workers who can deliver quality primary care and preventive health services effectively. We also need our community members to actively take part in protecting and preserving their own health.”

Santos, meanwhile, stressed that health must become a genuine government priority.

“We strongly believe Health care is a right and not a privilege that people have to beg for.”

But…Until When?

The Philippines remains a country where millions live with too few doctors and too many obstacles to care. The stories of physicians like Ang-Bon and Ermac illustrate both the dedication of those who serve and the structural barriers that undermine them.

The question is not whether the shortage exists, but the numbers speak for themselves. The question now is until when will Filipinos continue to endure a system where the accident of geography decides whether they can see a doctor in time?

Photo from Dr. John Myco Ermac

DISCLAIMER

This article provides general information and does not constitute medical advice. Consult your healthcare provider for personalized recommendations. If symptoms persist, consult your doctor.